To Eliminate Persistent Poverty, We Require Real Investment to Match the Existing Capacity

It used to be no one seemed to take much notice of rural parts of our country. I’ve noticed that in the past few years that has changed, but the attention has not all been positive. In fact, there is a less-than flattering view held by some people that goes something like: “Those places (Appalachia and others) are so poor everyone should pick up and move to other parts of the country.” Their view comes from the misguided belief that “those places” have received a great deal of money and assistance and are too far gone to become places of opportunity.

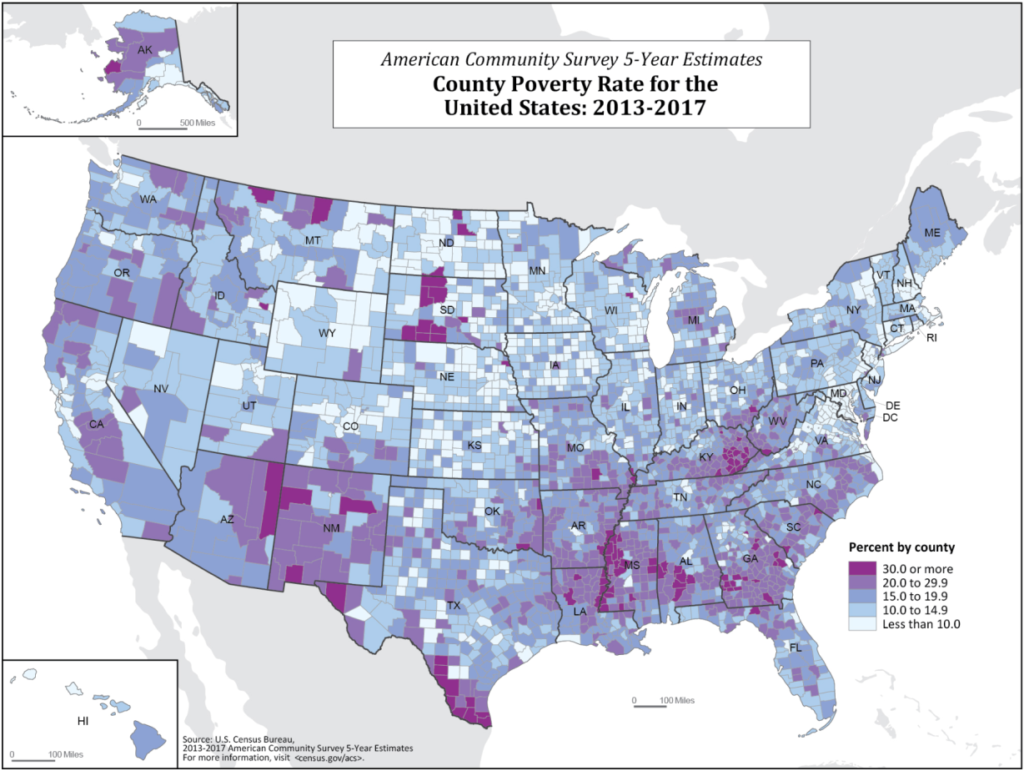

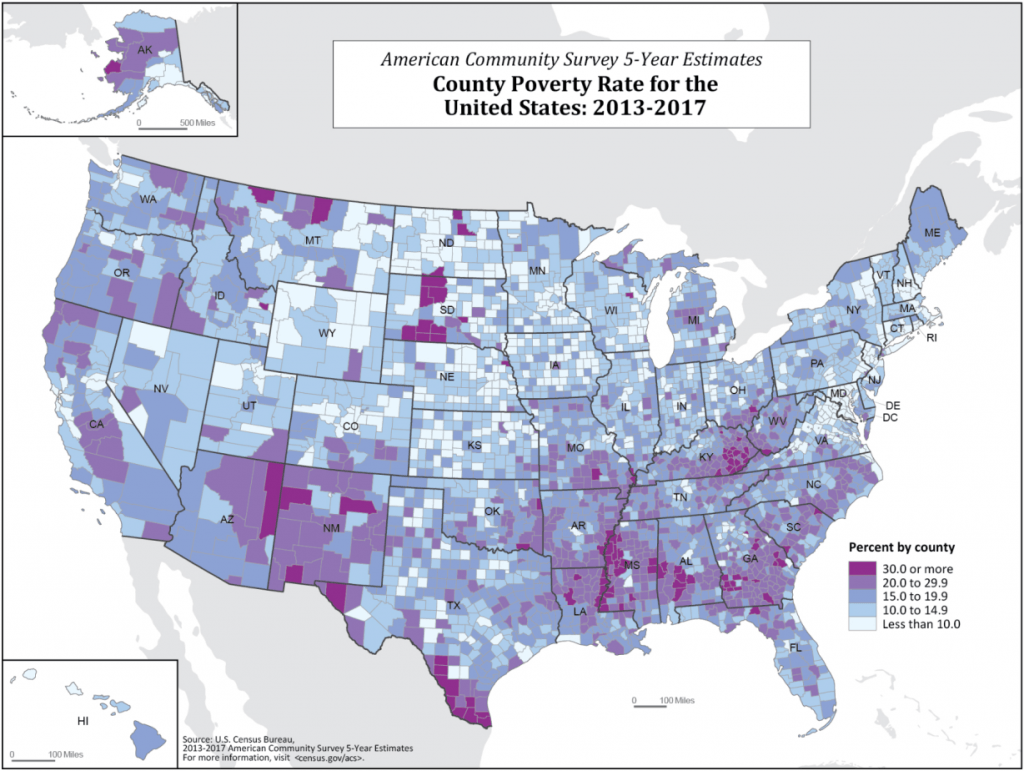

Of the 395 persistent poverty counties, 8 out of 10 persistent poverty counties are non-metro – home to nearly seven million people. The map below is based on the most recent American Communities Survey.

While high and persistent poverty exists throughout the nation, it is easy to see the regions and populations that are most often represented are Appalachia, along the Mexico border, the Delta and Deep South, the Central Valley of California, and Native American lands. Regions of deep persistent poverty were created by design, and today, the consequences of history manifests itself in distress and structural exclusion – high unemployment, a lack of access to banking services, a paucity of quality affordable housing and safe drinking water, lack of venture capital critical to the formation of small business. The persistent poverty we see today is the result of intention, either by economics or politics.

There is a strongly held belief that these same regions remain poor despite programs and targeted giving that should have resulted in progress out of poverty. The belief that there has been a substantial and equal investment in these areas is a myth. The fact is Philanthropic and Bank Investment lag in Persistent Poverty Areas.

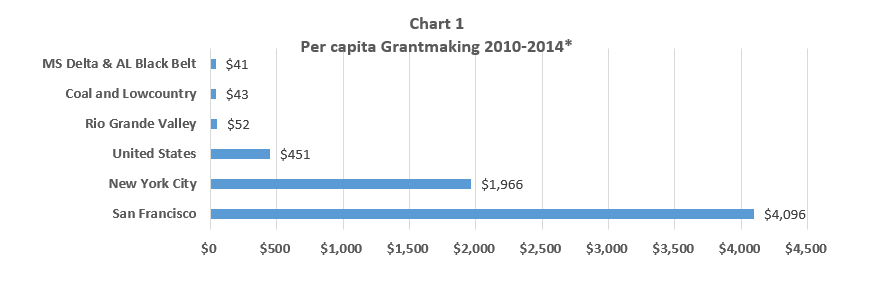

Despite the well-documented benefits of capital investment, particularly when deployed by CDFIs, such as Fahe, regions with large concentrations of persistent poverty lag behind large urban areas in philanthropic investment (Chart 1).

*Analysis for Native Communities was not available in this format

Underinvestment in rural persistent poverty regions, however, is not limited to philanthropy. Historically, particularly in large cities, banks have been the primary source of capital to support the growth of CDFIs and the subsequent strategies implemented to address unemployment, gaps in affordable housing, access to financial services and community infrastructure development. Due to structural deficiencies in the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) tying qualifying investments to branch locations, bank investment in rural CDFIs lag behind investment in CDFIs serving urban areas. In 2017, for example, only 27 cents of every dollar borrowed by rural CDFIS was from a bank in contrast to over half of funds borrowed by urban CDFIs (Chart 2).

To put some of this into context, the MacArthur Foundation has an initiative 100 and Change. Basically it’s an international competition for which the winner is awarded $100 million over 5 years. If an entire award was applied to only counties of persistent poverty, it would amount to $2.86 per person per year, and only for the 5 year period. In Appalachia that would increase philanthropic giving from $43 to almost $46 per person, and bringing us nowhere close to the national average of $451.

We have the solutions that work but not the investment to take them to scale.

In places of great need, financial investment serves as a critical intervention. Affordable housing programs offer opportunities for individuals and families to build assets through home purchase. Small business loan programs create jobs to address unemployment and poverty. When available, capital increases access to financial services that establish credit pathways and savings. Infrastructure development provides clean drinking water and safe disposal of waste water. Collectively, these strategies create wealth that stays in communities. We have the solutions that work but not the capital to take them to scale.

In the past 25 years, Fahe has been able to deploy nearly $1 billion across Appalachia, making use of the relatively little investment made to the region and helping to spread it with great impact. In fact, we reach over 80,000 people every year. While, I’m proud of the work that Fahe has accomplished in the region imagine what would be possible if saw an investment of $6 billion over the next 5 years. It’s more than Fahe can do alone, so we have joined with friends. The Partners for Rural Transformation are uniquely positioned to address the challenges of Persistent Poverty. Each of the Partners are CDFIs working in the most economically distressed regions of the country. Each has been successfully meeting the needs of local communities and people. From the development of entrepreneurs to the expansion of quality affordable housing, from increased access to financial services to more readily accessible, drinking water, these CDFIs leverage the power of finance to import capital into communities and regions that otherwise suffer from disinvestment, build human capacity to strengthen local economies and facilitate the assumption of agency and power in local people to determine a desired destiny. Additionally, in the rural poverty setting, we have built on this and learned to work collaboratively to extend our reach to the most remote corners of America.

What Can Be Done

Given the challenges facing persistent poverty areas and the clear funding gaps left by banks and philanthropy, deep, meaningful investments made with a sense of urgency are needed to create opportunity for both people and place.

The poorest regions of our country have never received the amount or type of investment needed to succeed. And our country cannot thrive until we invest in opportunity for all.