The Benefits Cliff: Eliminating Barriers to Transitioning Off Public Benefits

A 2018 study found that more than 22% of all working-age people in the United States were receiving some form of public assistance benefit, and with the economic disruption of the pandemic, that number has likely grown over the last few years. If, as a wealthy country, we are truly committed to prosperity for all of our people, then designing those public assistance benefits to provide pathways out of poverty is paramount. Fewer people in need of public assistance is best: individuals and families want the dignity of earning a living, and governments want fewer expenditures and larger tax bases. Solving the cliff issues will neither suddenly end the need for our support systems, nor force families into worse economic situations.

The “Benefits Cliff”: A disincentive to work and to wage increases.

The “Benefits Cliff” is when an individual would actually take home less money by accepting a job or a wage increase than they would if they turned it down. Faced with this choice, individuals make the rational economic decision to continue to support their families by remaining on the public assistance benefits.

Below is a chart outlining the financial mathematics of a family faced with the benefits cliff in East Tennessee several years ago. A single mother, with two children not yet of school age, was working 38 hours a week at $10 an hour. Her monthly income, including the value of public assistance benefits in the form of Supplemental Nutritional Assistance (SNAP, also known as “food stamps”), was $1,785. Childcare costs were mitigated by her enrollment in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. She had the opportunity to take up a salaried position at $26,000, but lost her eligibility for SNAP and TANF. The end result was a loss of more than $300 monthly, and nearly $4,000 a year compared to her previous situation. In this instance, the benefits cliff prevented career development for the individual; more extreme examples, often involving healthcare subsidy loss, can discourage employment altogether. This family is a relatively straightforward example of the cliff issue – they did not have cliff interactions with housing or health insurance, for example, which can affect similarly-situated families.

| Hourly Employment ($10/hr = $19,760) | Salaried Employment ($26,000) | Gain/Loss | |

| Monthly Wage (gross) | + $1,520 | + $2,166 | + $646 |

| Monthly SNAP Benefit | + $265 | + $0 | – $265 |

| Monthly Childcare Costs | – $0 (TANF) | – $700 | – $700 |

| Monthly Income (net) | $1,785 | $1,466 | – $319 |

The patchwork of public assistance benefits across levels of governments and targeted needs has created a system with different regulations for eligibility. Some programs determine that eligibility using fractions of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) which is determined nationally, and some use fractions of the Median Family Income determined locally (MFI, but often stated as AMI for Area Median Income). These two systems do not mesh neatly together, and each has its own failings. Fahe has written extensively about the failings of the MFI/AMI system, here. Additionally, this patchwork uses different fractions even within the same system to determine eligibility for different benefits (e.g. <100% of FPL versus <150% of FPL). Finally, enrollment in one benefit will often impact a family’s calculated income for eligibility in another benefit. For a family, this makes even determining when a loss of a given benefit will occur nearly impossible.

Many public policy proposals have focused on solving the benefits cliff by proposing the creation of a calculator to allow families to predict when these losses would occur (e.g. here, and here), but this does not address the cliff itself.

Solutions: Removing barriers by creating a bridge to program exit.

This section looks at some of the specific barriers to families facing the benefits cliff, and proposes ways to remove those barriers. The goal is to provide a bridge between full reliance on benefits and a complete exit. What we propose below are not entirely new ideas in the federal government: housing programs, largely, already acknowledge the problems of the benefits cliff and work to mitigate them. The HUD Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher program, for instance, scales the rent burden of a voucher holder directly to their income, ensuring that there are no hard cliffs where the loss of a voucher causes a new financial stress. Other federal agencies, and other programs within the HUD portfolio, can learn important lessons from the housing programs.

Because families with young children, especially those headed by a single parent, are more likely to receive public assistance benefits, one of the largest hurdles to exiting to employment is childcare, both its availability and cost. Some state governments are beginning to recognize the severity of the cliff and are making changes to childcare supports to mitigate its effect. If private childcare is needed, the cost burden imposed by engaging it can be substantial and is often on a per-child basis. As indicated by the East Tennessee example shared above, this cost can more than wipe out even substantial increases in wages.

- Communities seeking to eliminate the benefits cliff locally could invest in low-cost childcare provision for their residents,

- Regulatory bodies governing existing public assistance benefits that provide subsidies for childcare could seek to extend those subsidies to enrollees for a period of years following such an enrollees’ exit, and/or

Nationally, we could enact legislation that has as its goal the affordability of childcare for every American family.

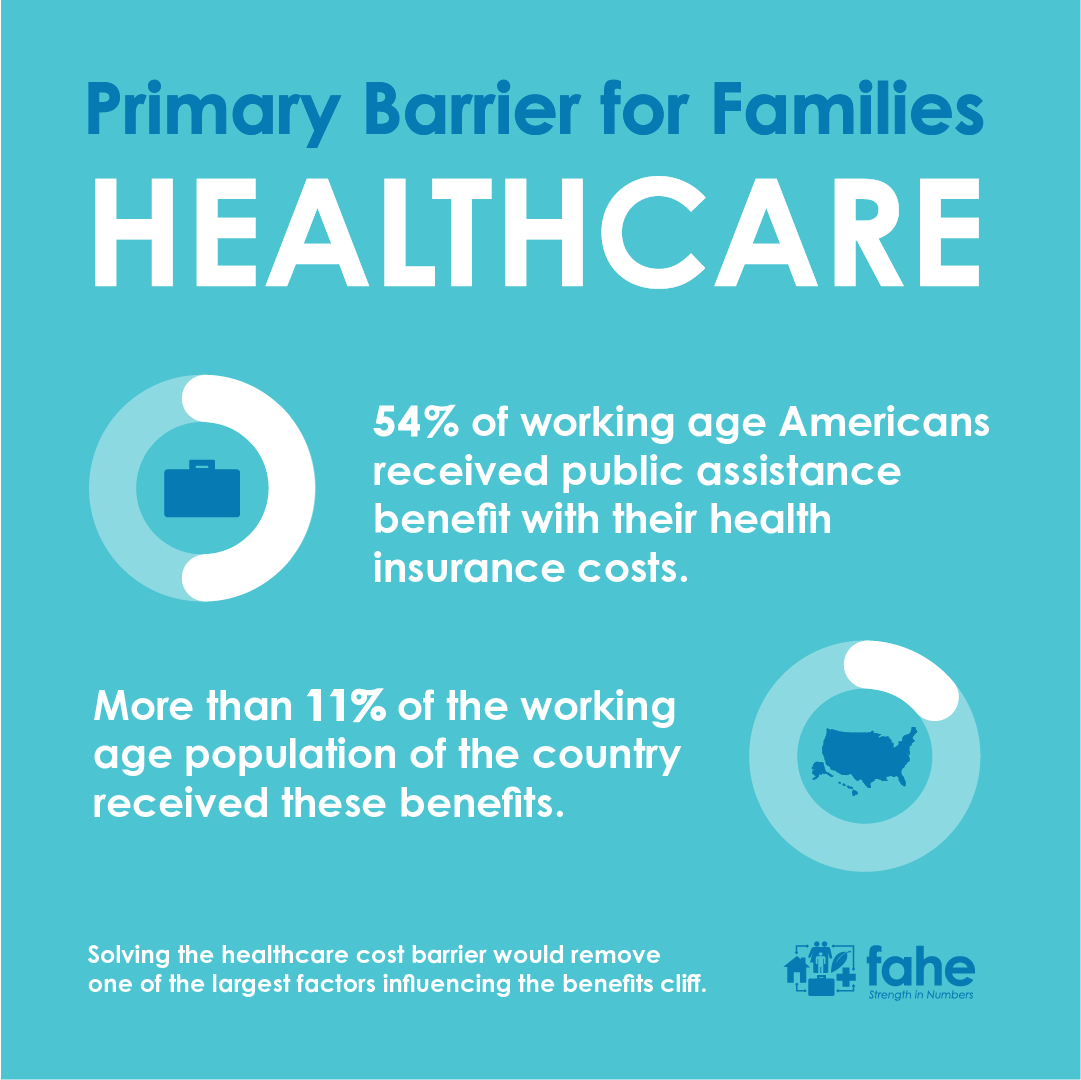

Similar to childcare, healthcare costs are a primary burden to families facing the benefits cliff. More than 54% of working age Americans who received some public assistance benefit received assistance with their health insurance costs, that’s more than 11% of the working age population of the country. Solving the healthcare cost barrier would remove one of the largest factors influencing the benefits cliff.

- Regulatory bodies governing existing public assistance benefits that provide subsidies for health insurance could seek to extend those subsidies to enrollees for a period of years following such an enrollees’ exit, or until a job is accepted which provides the same cost of health insurance premiums, and/or

- Nationally, we could enact legislation that has as its goal the affordability of healthcare for every American family.

Transportation costs associated with employment are also a barrier, and vary widely with community composition and commuting distance. The national average for commuting costs in 2017 was $2,226. The primary effect of transportation cost increases is on complete employment re-entry. In rural locations where the vast majority of workers commute by car, entry to the workforce can require up-front capital to purchase a vehicle.

- Regulations governing public assistance benefits could allow increased asset limits for existing enrollees to encourage savings development, easing the negative effect of acute capital needs on workforce entry, or

- Those bodies could disregard transportation costs from income for purposes of benefit calculations.

A barrier exists when training is sought by the primary earner of a family, or by another family member (including children) that comes with income. For example, a teenager in a family receiving public assistance benefits who wants to enroll in a workforce training program like YouthBuild. The stipend that comes with the YouthBuild enrollment can threaten a family with a benefits cliff, and prevent the enrollment of the child in the program. This hurts not only the immediate earning potential of the family, but the long-term career trajectory of the child.

- Regulations governing public assistance benefits could cause workforce development-related family income to be excluded from all income calculations. (Some program regulations already discount certain forms of income from their calculations – e.g. HUD has sixteen exemptions, including things like student aid for dependent children).

While in decline since its political heyday in the 1990’s, public policy interest in the impacts of public assistance benefits on family formation and marriage rates continues to this day. Most scholars agree that there is some effect of benefits on the choices of low-income Americans to marry, but the data is sparse. The best evidence of a disincentive to marriage is found in a narrow segment of the population (couples with relatively high incomes for benefit enrollment, who are both separately enrolled in both SNAP and Medicaid, and who have a child under two years old). No other segment of the population demonstrated a measurable effect.

Conversely, the same study found that in a survey of Americans, almost a third stated they personally knew someone who has not married for fear of losing means-tested benefits. This latter data point fits with our understanding as on-the-ground experts in program deployment. It is an extension of the benefits cliff: two incomes mean lower benefits that are not compensated for by the increased income of the second earner. Fahe recognizes that current public policy disincentivizes household formation and marriage among low income Americans. We believe that those disincentives should be removed, allowing people to make these very personal decisions without fear of losing financial stability.

- If the measurable disincentivizing effect of SNAP and Medicaid on marriages is correct, then targeted changes to those programs’ regulations can counteract them (e.g. increasing income thresholds for married couples with children above those for single parent households with children), or

- Looking more expansively at the public benefits system as a whole, regulators could mirror the US tax code’s system of separate schedules for those who are married and those who are unmarried. The separate schedules for income limits could be designed such that it removed the disincentive to marriage.

Solutions: Systemic approaches.

Because of the patchwork design of our public assistance benefits system, and because of the deeply intertwined way one program influences eligibility for others, addressing individual drivers of the benefits cliff may be less than transformational. Instead, the federal government could look across program lines to address systemic changes.

Referenced above, allowing for the building of savings accounts and asset building by families could have a dynamic effect. It would empower them to address emergency expenses without recourse to high interest rate loans that further reduce their net incomes. It would also enable families to exit programs on more solid financial footings, or even provide the down payment for an affordable mortgage. Federal programs like Supplemental Security Income have federally mandated asset limits, and while others like SNAP and TANF allow some state leeway, all are too low to allow real asset building or financial security. For example, the asset limit for SSI has increased by only $500 since 1972, nearly five times less than an inflation-adjusted number would have increased. For programs over which it has total control, the federal government could increase asset limits to match the inflation-adjusted numbers, and create automatic increases to account for inflation in the future. For programs with shared state and federal authority, policy makers could pursue program changes based on current best practices from their peer states – which include removing asset limits on programs designed as temporary safety nets (like SNAP and TANF). Case in point: causing an otherwise eligible family to sell their car to access TANF will limit that family’s ability to exit the program successfully, as it is more difficult to achieve re-employment if you have lost your transportation.

With regard to asset limits, Individual Development Accounts (IDAs) bear specific mention. This unique program, which allows low income individuals to receive match funding to savings accounts for specific uses (buying a home, paying for education, or starting a business), has enrollment asset limits of $5,000 – often less than the value of a reliable family car. And while the income from the account is not counted against an individual for purposes of other program enrollment, the value of the asset can be. Lawmakers could strengthen the anti-poverty power of IDAs by entirely ignoring these accounts when determining eligibility of the holder for other programs. IDAs can be the pathway off of public assistance benefits if we allow them to be.

The steepness, or severity, of decreases in benefits on a program-by-program basis varies. Some programs, like SNAP and many federal rental assistance programs, decrease the value of benefits slowly, in line with increases in income. Other programs have hard cliffs, with a single wage raise being the difference between full benefit and ineligibility [e.g. Special Supplemental Nutritional Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)]. Governments could faze out hard cliffs in favor of instituting sliding scales of benefit tied to income. Further, they could ensure that those sliding scales expand beyond just the very poor, allowing enrollees to retain decreasing benefits up to 200%, 300%, or even 400% of the Federal Poverty Line, as Fahe proposed in a recent white paper on the need for investment in jobs through home repair.

Governments at all levels could work to make eligibility measurements standard across all programs. This could start with the use of a single measurement of incomes. Problems exist with both the FPL system (a national number, does not take local data into account) and the MFI/AMI system (disadvantages areas with concentrated rural poverty). A uniform approach to eligibility could lessen confusion for families faced with decisions, and eliminate program mis-matches and inequitable impacts based on geography.

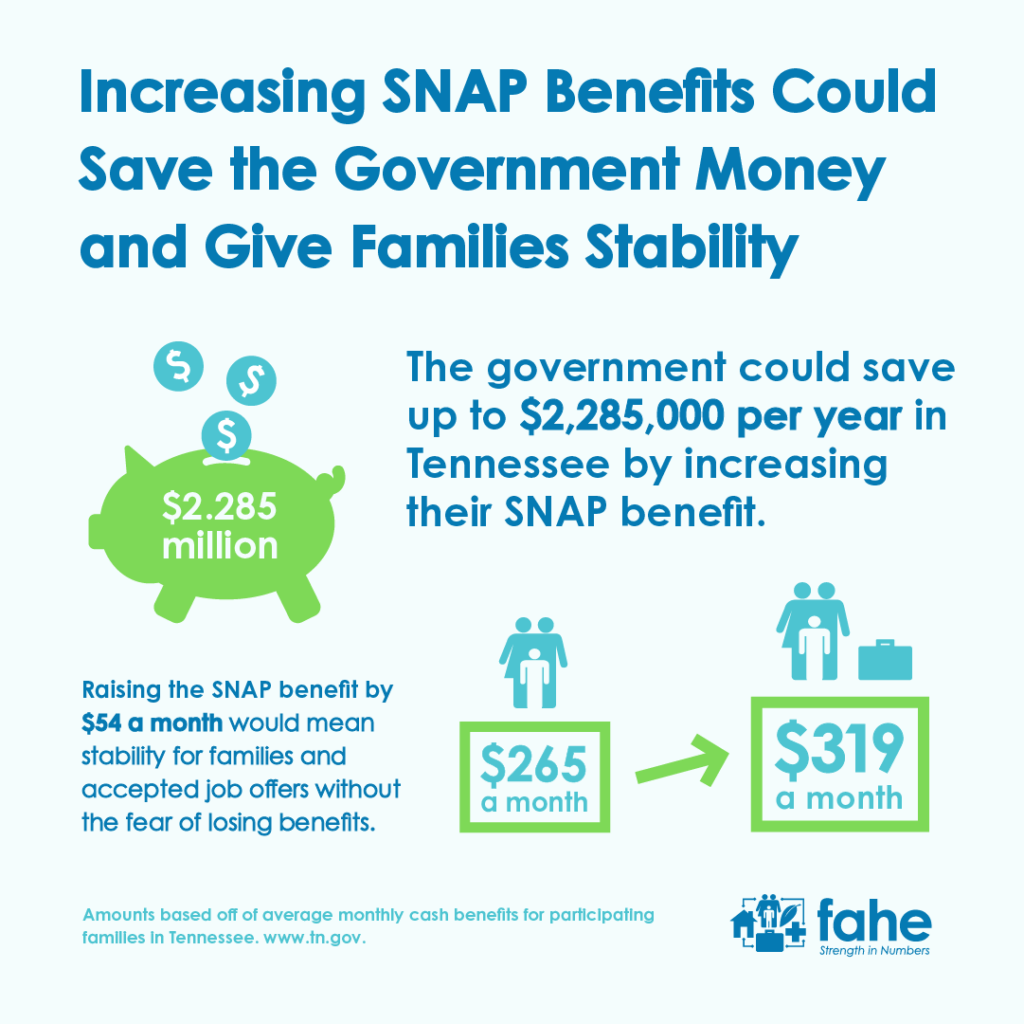

Finally, if governments are unwilling to cause eligibility measurements to be uniform across programs, there is a middle ground option that would ease burdens on families, drive program exits, and save government expenditures. Governments could institute a guarantee for enrollees that increased wages will never result in a loss of net income. This guarantee might result in the requirement of a case-by-case review of circumstances and the maintenance of payments for those who otherwise might be considered over-income, but would ensure that no one faced with a benefits cliff would choose to turn down employment or a higher wage simply for financial reasons. If we return to our example family in East Tennessee, we can see that actually increasing the SNAP benefit by $54 a month (to $319 from $265, instead of eliminating it) would allow the government to save the entirety of the TANF payment (estimated average TN monthly payment of $387). In this hypothetical, the government would have saved $3,996 a year on this family alone, and the mother would have been able to take the job without fear for her family’s stability. In other words, from the government’s perspective – the cost of continuing to provide subsidy to the now-working mother constitutes a savings over what it was previously spending, and enables a further savings in the months and years to come as the family’s financial stability and earning power increase.

| Hourly Employment ($10/hr = $19,760) | Salaried Employment ($26,000) | Proposed Salaried + Transitional Supports | |

| Monthly Wage (gross) | + $1,520 | + $2,166 | + $2,166 |

| Monthly SNAP Benefit | + $265 | + $0 (Loss of SNAP) | + $319 (Increased SNAP) |

| Monthly Childcare Costs | – $0 (TANF) | – $700 (loss of TANF) | – $700 (Loss of TANF) |

| Monthly Income (net) | $1,785 | $1,466 | $1,785 |

| Hourly Employment Government Costs | Proposed Salaried + Transitional Supports Government Costs | Government Increase/Savings | |

| Monthly SNAP Benefit | $265 | $319 (Increased SNAP) | + $54 |

| Monthly TN Avg. TANF | $387 | $0 (TANF Savings) | – $387 |

| Total, Monthly | $652 | $319 (Increased SNAP) | – $333 |

| Total, Annual | $7,824 | $3,828 | – $3,996 |

In Table 3, we see the governmental savings potential for one specific family in Tennessee. If we take this family as an average case, we can determine the annual savings across the entire state if this proposal was adopted. There are currently 572 families in TN receiving TANF that are already working – these are the most likely candidates for increased incomes and new job offers in the current employment market. If every one of those families, and no others of the 13,577 families currently on TANF but not working, received similar offers of increased income, the government could save up to $2,285,000 per year simply by increasing their SNAP benefit.

Looking nationally, 25.6% of the 1.093 million TANF recipient families in FY2019 had an employed adult, meaning 286,373 families had such a working adult. Total spending for the TANF program was $31,552,168,000 in FY2020, making the national average per-family cost $28,867. The TN example required a 20% increase in the SNAP benefit; expanding that to the national average for SNAP ($2,868 per year) means a required cost increase of $573 per family per year. Taken all together, the maximum savings potential nationally of this proposal is $8.1 billion. While the gains from this policy change are dramatic, it leaves in place the patchwork of eligibility measurements and regulations that cause the benefits cliff in the first place.

Solutions: Incentivizing exit from public assistance benefits.

Legislators and lawmakers uncomfortable with providing long-term post-exit support to enrollees, or with allowing for the accumulation of savings while enrolled, could instead consider short-term “jump start” periods where benefits are actually increased for a short term when a family experiences an increase in income. In this model, the jump start payments are used as a one-time incentive for families to seek and accept work or wage increases that would cause them to lose benefits.

In theory, the upfront increase of income could cover the one-time expenses associated with employment (down payments on vehicles, uniforms/tools/safety gear purchase) and incentivize program exit. However, this would likely only work in marginal cases of individuals timing-off of benefits, for example in the case of a child aging out of health care subsidies. To be an attractive financial incentive to governments, the jump start payments would need to be less of an expenditure than the remaining time on the benefits; and likewise with the family, the increase of income would have to be substantial enough to compensate for the loss of the medium-term stability of the payment or benefit.

Public policy professionals and governments currently struggling with incentivizing “return-to-work” following the coronavirus pandemic are facing many of the same pressures and proposing many of the same solutions as those we propose here. One anomaly however is the proposal to incentivize people to take open jobs with a one-time cash payment. These usually take the form of flat payments for either engaging in full- or part-time employment ($1,600 in CO for full-time, in ID it is $1,500 for full- and $750 for part-time). It is too early to have data on the efficacy of these programs, but they are proving popular and funds have been quickly depleted. Some states have instituted paperwork requirements for applicants to prove they have taken a job, and stayed employed there for a period of time, in order to receive the payments. Using this same rationale, lawmakers could create a national incentive program that provided a flat payment for people facing a benefits cliff. If the payment was large enough, it would serve as an attractive incentive to move people back to work.

Crucially, such a payment alone would not solve the issue of the benefits cliff. To be successful in the long-term, it must be used in conjunction with the barrier-removing policy proposals in this paper. The removal of barriers makes the move to work possible, the incentive makes it attractive.