Closing the Digital Divide in Appalachia

How Policymakers can Maximize Historic Broadband Investments to Bring

Virtual Opportunity to Every Community

On February 4th, Fahe submitted public comments to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) regarding its guidelines for $45 billion in state-allocated federal broadband funding from the recently-enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The Appalachian region faces unique challenges, but drawing from Fahe’s board-approved Broadband Policy position, our Network provided substantive feedback and community-level insights on the best ways to deploy these resources to ensure our region can fully realize the benefits of this historic investment in digital connectivity.

As communities across the region begin to chart out their strategies for leveraging this investment, Fahe will be documenting an ongoing series exploring new ideas and lessons learned to help maximize the potential of these resources in finally closing the digital divide.

Quality Infrastructure Based on Reliable Data

As noted by the U.S. Treasury and supported by Fahe, extending true high-speed broadband service requires maintaining certain speed and quality standards necessary to ensure reliable, consistent connectivity. As Fahe has documented, 100 Mbps download and 20 Mbps upload are the minimum acceptable speeds for a community to participate in modern digital commerce and virtual economic transactions, and in commercial centers, 100 Mbps download/100 Mbps upload speeds are needed. These performance thresholds are not only essential for attracting emerging technology industries that rely on unbroken, high-bandwidth data access, but also for other local merchants and employers to process even routine transactions and readily interact with remote marketplaces.

Moreover, Fahe also highlighted that the current landscape of broadband inequity is partially driven by poor broadband mapping. The FCC’s broadband map is widely considered to be a flawed measure of high-speed data availability. Its current process largely relies on an honor system for internet service providers to self-report their own data speeds to the agency, and its mapping features tend to count entire census tracts and adjacent areas as being technically “served” when only a small fraction of the local residents may actually have broadband access. This mapping gap can be particularly problematic for rural areas, as the vast majority of a sparsely-populated community can be overlooked even if only one residence in its large geographic footprint has the ability to access broadband services.

As a result, policymakers and telecom regulators cannot accurately identify the full scope of the digital access problem if they don’t know where our most digitally isolated neighbors actually live. To address this problem, Fahe recommended that the NTIA coordinate with state broadband commissions, many of whom have created their own, more reliable broadband maps. In Fahe’s service area alone, Alabama, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Virginia have either developed, or are in the process of developing, their own state-informed broadband service maps. Enhancing this kind of collaboration between state and federal stakeholders can help policymakers and private-sector providers alike gain a more accurate, informed perspective on the extent of our underserved communities and deploy targeted solutions to high-need areas.

Invest Right—Invest Once

In order to solve the challenges presented by Appalachia’s unique characteristics, Fahe’s proposed solutions are based on an “Invest Right – Invest Once” approach. Our region’s mountainous topography and diverse geographic distributions of local populations bring with them unusual challenges and special considerations for how high-speed services can effectively reach individual households. While wireless coverage may have some role, reception quality and latency issues necessitate broadband projects based on hardline and fiber networks rather than relying solely on 5G or other wireless technologies. Although physically laying hardline networks to some remote communities can pose cost and logistical challenges, the funding resources in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) should be devoted to delivering service to geographies where ordinary market forces likely wouldn’t sustain commercial providers’ deployment costs.

Prioritizing Equity

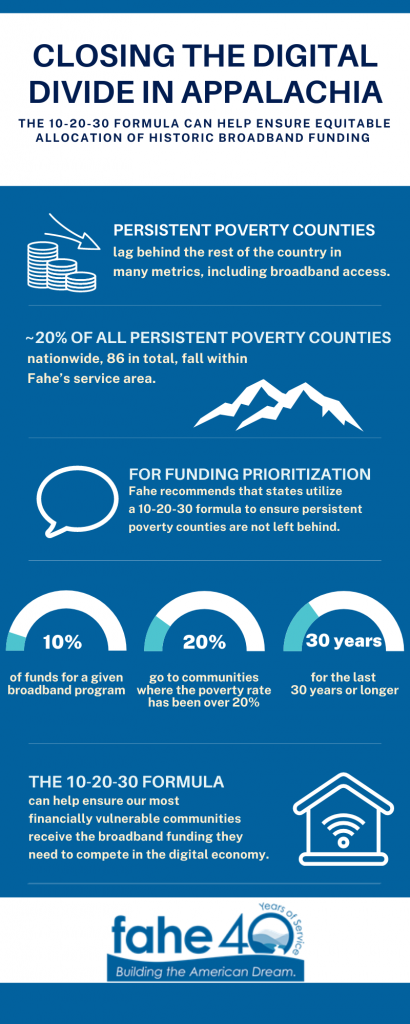

Another point of emphasis in Fahe’s comments was funding prioritization for persistent poverty counties. Persistent poverty counties lag behind the rest of the country in many metrics, including broadband access. Almost 1/5th of all persistent poverty counties nationwide, 86 in total, fall within the Appalachian states in which Fahe is active. To ensure persistent poverty counties are not left behind, Fahe recommended that NTIA guidelines for states utilize a 10-20-30 formula for funding prioritization. This formula would require that 10% of funds for a given broadband program go to communities where the poverty rate has been over 20% for the last 30 years or longer. Fahe also recommended that matching requirements for grants be waived for persistent poverty counties. As our Partners for Rural Transformation have previously observed, poor, rural areas generally do not enjoy the local resources to accommodate matching funds requirements. In fact, the IIJA’s $2 billion allocation for the USDA’s Rural Utility Services ReConnect Program already explicitly waives such matching dollars requirements for persistent poverty counties. The 10-20-30 formula, in conjunction with waived matching requirements, can therefore provide an added safeguard to ensure our most financially vulnerable communities receive the broadband funding they need to compete in the digital economy.

Relatedly, Fahe commented on NTIA’s definition of an “eligible subscriber,” or what factors should qualify an individual or household for a low-cost broadband assistance option. In our comments, Fahe noted that studies have shown low-income consumers can generally afford to pay about $10 per month for broadband service. If NTIA can expand the FCC’s Emergency Broadband Benefit to any family receiving federal low-income assistance, such as SNAP, Medicaid, or housing assistance, it could also provide a pathway to overcome the cost barriers that can similarly obstruct access to high-speed data service.

Accountability & Leveraging Local Stakeholders

Accountability for construction timelines, quality, and maintenance standards has also proven to be problematic in previous broadband initiatives. To address these potential concerns, Fahe recommended a verification process to ensure quality-control systems be implemented that help guarantee IIJA-funded projects are constructed on time and in accordance with NTIA and state guidelines. For example, Fahe advised NTIA to coordinate with the FCC in order to create rules that would preclude funding any entity that has previously won federal award dollars and then failed to fully perform their promised upgrades. Fahe also called for NTIA to encourage states to fund projects from locally-based organizations such as nonprofits, co-ops, and municipal systems, all of which know their regions well and have more intimate connections to the communities they seek to serve.

As the long-term financial and social impacts of the pandemic begin to come into focus, it is apparent that access to virtual markets and digital connectivity will have an ever-appreciating value in the modern economy. Not only will high-speed networks be required for many families to access job, educational, and medical services, but the communities in which they live will experience increasing pressure to compete for new businesses and better-trained workforces in a digitally-dependent economy. Through these comments, it is our hope that NTIA will channel this historic broadband investment opportunity to the neighborhoods that most need a long-term investment. By helping these communities become technologically competitive, we can unlock the promise of the American Dream across Appalachia and across the nation.