Calculating Inequality: The Paradox of Rural Poverty and Federal Income Limits

Policymakers have long grappled with the challenge of judiciously marshalling taxpayer resources to support the communities and programs where public investments will have the strongest impact. In fact, many federally-funded housing and community development programs target their efforts based on the incomes of the people seeking assistance. Applicants are deemed either eligible or ineligible based on how their income compares to their neighbors in order to prioritize the households that have the greatest financial need for assistance. However, what if the underlying income calculations on which policymakers rely to precisely target federal aid are fundamentally flawed?

To illustrate, in Perry County, Kentucky an average hard-working nurse and single mother making around $53,000 per year can often struggle to make ends meet in her family budget, particularly for costly necessities like mortgage payments and long-term housing. Although federal resources exist for residents in exactly her situation, she, like many Americans, may find herself sandwiched between earning too much income to technically qualify for federal housing programs, yet also making too little to realistically afford a modest, safe family home.

Income limits such as these are used to determine eligibility thresholds for which families can access certain federal programs and resources, including low-income housing assistance. The limits are based on the median family income calculated in a given county and are designed to channel the limited pool of available federal funds to households earning incomes below the limit. However, this localized approach can produce some problematic geographic contradictions for comparable communities in neighboring states when one has a concentration of low-income rural areas while the other is relatively wealthier.

For example, the median income calculated for Perry County, Kentucky is $45,700, significantly less than the roughly $70,000 assessed for similar communities just a few hours away in neighboring Ohio. A family making $53,000 annually, like the working nurse and single mother, would be considered low-income in Ohio and, therefore, eligible to access to low-income housing assistance. However, because she lives south of the Ohio River, where her state’s average median income is calculated at a significantly lower level, she does not qualify for federal assistance under the existing formula.

Setting aside the clear issues of fairness and program efficacy, this uneven application of essential financial aid for identically-situated families separated only by a state border and a relatively short car ride creates a perverse incentive structure that further erodes economic stability for communities already beset by generations of pervasive poverty. If the nurse in Perry County could access federal housing assistance under the same calculation as nearby families in Ohio, she would not only be able to afford safe and adequate family housing for herself and her children, but also would be more likely to remain in her hometown and raise her family locally. Construction for her home and her comparably-positioned neighbors would, in turn, increase modernized housing stock in the area and offer quality employment opportunities for local workers. However, the current paradigm offers little anchoring incentive to keep the nurse and her family in her rural Kentucky hometown, draining workforce talent and stable family incomes from an already disadvantaged community and denying her neighbors, employers, schools, and local institutions of the beneficial economic ripple effects.

Anticipating geographic inequities, Congress originally established so-called state “floors” in an attempt to prevent income eligibility disparities across similar localities. Under these state floor provisions, any county with a median family income below the statewide average can instead use the statewide non-metropolitan low-income threshold, rather than that of the county, in order to more accurately measure its families’ income eligibility for federal assistance. In practice, the state floor substitution has worked well in places like California and New York, which benefit from relatively affluent non-metropolitan areas and only a few isolated persistent poverty counties.

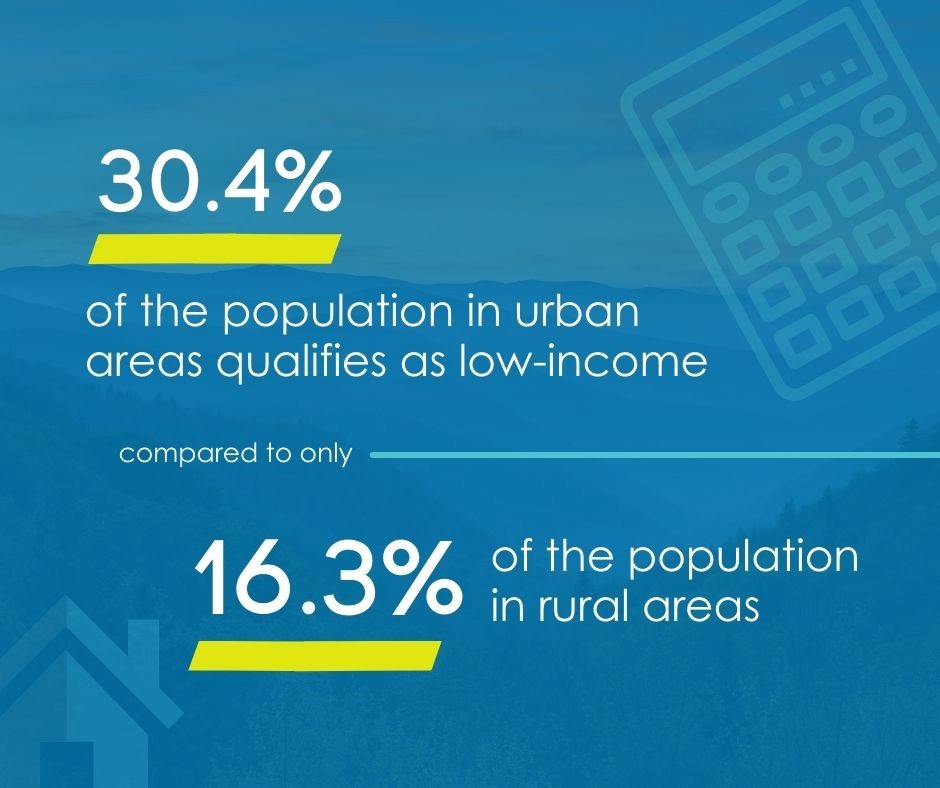

However, this remedy quickly falls apart in states like Kentucky, where widespread concentrations of rural poverty lower the statewide median family income calculation. Even with a floor, the scarcity of more affluent suburban, exurban, and non-metropolitan communities to comparably bolster the statewide non-metropolitan median income figures offers little benefit for the state’s predominately poorer communities in substantially rural areas. In fact, evidence of this inequity is readily observable in nationally-referenced income data, where 30.4% of the population in urban areas qualifies as “low-income” compared to only 16.3% of the population in rural areas.

While efficiently targeting federal investments to the most financially vulnerable families may make for sound policy rationale, the realities of the current system have produced serious inequalities for those who can least afford to shoulder them. Even beyond Appalachia, the disparate outcomes of these flawed eligibility calculations are connected to a legacy of racial injustice, particularly for the Mississippi Delta, the Colonias, and in Tribal lands where the concentration of rural poverty overlaps with communities of color.

In order to rectify the inequities caused by the current system, Congress should derive income limits for federal program eligibility from the higher of the county, state, or national non-metropolitan median incomes rather than restricting them to solely state or local assessments. Fahe’s own extensive research on this issue shows that a nationally-referenced measurement for income eligibility would increase the income limits for 998 counties across the country, yielding an immediate and transformative economic benefit for millions of Americans. It’s why our Network continues to prioritize this much-needed reform with policymakers in the hopes of empowering the families they serve across Appalachia with access to much-needed federal investments—investments for which they would otherwise qualify if they simply lived in more affluent communities.

American Rescue Plan and the Homeowners Assistance Fund

The pandemic has only exacerbated economic disparities for rural communities, and the federal response has likewise underscored the shortcomings of the existing methodologies for determining income-based financial assistance eligibility. Created by the recently-enacted American Rescue Plan Act, the Homeowner Assistance Fund provides financial resources to each state that can be distributed to homeowners struggling to remain in their homes as a result of coronavirus-driven economic displacement. Qualifying families can use HAF relief dollars for mortgage payments or other related expenses like utility bills.

In an apparent nod to the pitfalls of the existing income eligibility system, Congress prudently established that households making less than 100% of the National Median Income had priority in accessing HAF aid. As such, families seeking relief under the provisions of the HAF program would be spared the inequities that afflict other federal housing assistance initiatives. Unfortunately, the Treasury Department has since limited the program to homeowners making less than 150% of their locality’s median income. For nearly 600 counties across 17 states, that 150% uptick in the qualifying threshold for HAF assistance puts their income eligibility limit below the national median as initially designed by Congress. Although the Treasury Department may ultimately revise its regulations to better adhere to congressional intent, the issue remains unresolved for the other federal programs falling outside the scope of pandemic relief.

The American Rescue Plan Act is a sweeping piece of legislation that has the potential to inject major federal relief dollars and public investments into some of the most disadvantaged communities in our nation. However, to ensure that funds are truly getting to where Congress intended them, the Treasury Department’s limit requires revision.

The unfairness in the way community development funding is diluted and diverted away from our country’s poorest rural areas needlessly excludes millions of families in these communities around the country from achieving their American Dream, many of whom are Americans of color. Imagine the country we could build if we instead took an inclusive approach, rectifying existing unfairness as part of a greater effort to revitalize the economy for all Americans, no matter their race or place. The adoption of a national floor for federal housing and community development investments across the board will help millions of Americans rebuild following the pandemic and set an important precedent for targeting future assistance initiatives.